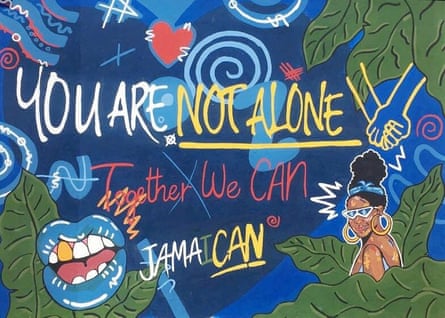

“JamaiCAN,” reads a mural at one of the entrance gates to Bellevue, Jamaica’s only psychiatric hospital. The name of the old powder-pink building near Kingston’s upmarket waterfront is recognisable to any Jamaican and is shrouded in stigma.

Built as a colonial lunatic asylum in the 19th century, it had been a tool of political repression, serving as prison for Rastafarian luminaries, forefathers of pan-Africanism, and other Jamaicans who challenged British racial oppression. After independence, media coverage of Bellevue was dominated by stories of poor treatment of patients and threadbare facilities.

Staff and directors are today determined to transform the hospital into a modern treatment centre, building on decades of Jamaica’s pioneering mental health policies. But one barrier keeps emerging: resources.

“It’s really challenging to get focus on non-communicable diseases, and mental health is a fraction of the focus on non-communicable diseases,” says Ishtar Govia, a member of Bellevue’s board of directors and a researcher at the University of the West Indies.

Quick Guide

A common condition

Show

The human toll of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is huge and rising. These illnesses end the lives of approximately 41 million of the 56 million people who die every year – and three quarters of them are in the developing world.

NCDs are simply that; unlike, say, a virus, you can’t catch them. Instead, they are caused by a combination of genetic, physiological, environmental and behavioural factors. The main types are cancers, chronic respiratory illnesses, diabetes and cardiovascular disease – heart attacks and stroke. Approximately 80{35112b74ca1a6bc4decb6697edde3f9edcc1b44915f2ccb9995df8df6b4364bc} are preventable, and all are on the rise, spreading inexorably around the world as ageing populations and lifestyles pushed by economic growth and urbanisation make being unhealthy a global phenomenon.

NCDs, once seen as illnesses of the wealthy, now have a grip on the poor. Disease, disability and death are perfectly designed to create and widen inequality – and being poor makes it less likely you will be diagnosed accurately or treated.

Investment in tackling these common and chronic conditions that kill 71{35112b74ca1a6bc4decb6697edde3f9edcc1b44915f2ccb9995df8df6b4364bc} of us is incredibly low, while the cost to families, economies and communities is staggeringly high.

In low-income countries NCDs – typically slow and debilitating illnesses – are seeing a fraction of the money needed being invested or donated. Attention remains focused on the threats from communicable diseases, yet cancer death rates have long sped past the death toll from malaria, TB and HIV/Aids combined.

‘A common condition’ is a Guardian series reporting on NCDs in the developing world: their prevalence, the solutions, the causes and consequences, telling the stories of people living with these illnesses.

Tracy McVeigh, editor

Up to 80{35112b74ca1a6bc4decb6697edde3f9edcc1b44915f2ccb9995df8df6b4364bc} of people with mental disorders live in low and middle-income countries. And while mental health has received increased attention after the Covid pandemic, this has not been reflected in global funding for psychiatric health, says Rebecca Gribble from Georgetown University.

According to her research, only 0.3{35112b74ca1a6bc4decb6697edde3f9edcc1b44915f2ccb9995df8df6b4364bc} of global health development funding is dedicated solely to mental health projects.

“Donors like to put their money towards things that get quantifiable results,” Gribble says. “With mental health that is more difficult to measure than with viruses, for example.”

However Jamaica, unlike many low and middle-income countries, has been at the forefront of mental health innovation over the past 50 years. After gaining independence in 1962, Jamaica became one of the first countries in the world to take decisive steps to deinstitutionalise its mental health system and integrate it into primary healthcare, despite limited resources.

Today, up to 80{35112b74ca1a6bc4decb6697edde3f9edcc1b44915f2ccb9995df8df6b4364bc} of Jamaicans with chronic mental illness are not hospitalised in Bellevue but receive treatment in local health centres or at home, thanks to mobile teams made up of psychiatrists and specially trained nurses.

This approach provides a useful task-sharing model for countries looking to restructure their mental health services, says André van Rensburg from the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, who has been researching deinstitionalisation in low and middle-income countries.

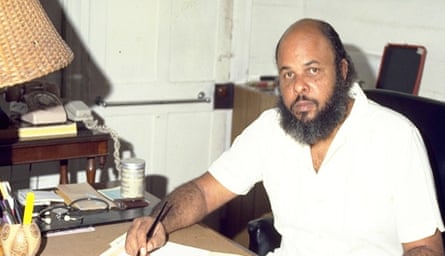

The Jamaican model was introduced by the late Professor Frederick Hickling, who was the senior medical officer at Bellevue throughout the 1970s and 1980s – the highest psychiatric post in the country.

Hickling was determined to move the country away from the custodial treatment style inherited from Britain, whereby mentally ill patients were detained in hospitals against their will – as is still the case in many low and middle-income countries.

“Post independence we had limited financial resources and a population traumatised by colonialism and the legacy of slavery,” says Geoffrey Walcott from the Caribbean Institute of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, founded by Hickling. “We had to find novel ways to restructure our system.”

By allowing patients to receive healthcare without being committed to Bellevue, Hickling hoped to avoid the shame associated with mental illness while making treatment more accessible and cost-effective. Nearly half of Jamaicans live in rural areas, a costly journey away from Kingston’s Bellevue, while fewer than 10{35112b74ca1a6bc4decb6697edde3f9edcc1b44915f2ccb9995df8df6b4364bc} own a car.

Hickling also sought to minimise involuntary treatment.

“What we found is that if patients are part of the decision-making process and accept treatment, they are more likely to recover and remain well over a long-term period,” says Walcott, a former student of Hickling. “The biggest cause of relapse, especially for patients with schizophrenia, is non-compliance with treatment. When a patient is onboard with their medication, the relapse rate can be cut from 50{35112b74ca1a6bc4decb6697edde3f9edcc1b44915f2ccb9995df8df6b4364bc} to 3{35112b74ca1a6bc4decb6697edde3f9edcc1b44915f2ccb9995df8df6b4364bc}.”

Walcott recalls attending to a mentally ill man, armed with a knife and a machete, who had been apprehended by the police. “We opted not to take him involuntarily to a hospital and, while keeping his machete and his knife, he accepted treatment,” Walcott says.

After three weeks of treatment the man was lucid enough to cooperate with Bellevue’s social work team. “The team was able to find his brother and within six months the man was reintegrated into his family while taking long-acting injectables to manage his condition. Today, deinstutionalisation is baked into our healthcare model.”

But while Jamaica has found innovative ways to deliver mental healthcare to its citizens, this has not meant the end of challenges for the island as resources remain scarce.

after newsletter promotion

“I am grateful that my son is not wasting away in some hospital,” says Yvonne McKenzie, whose son Andrew, 39, has bipolar disorder. “But I don’t feel supported by the system. I feel alone.”

For McKenzie, the mental healthcare model which centres on family and community cooperation means that, in the face of limited resources, the responsibility for managing illness can disproportionately fall on women.

“I have seen my son’s psychiatrist more times than I can count, but I don’t think Andrew’s dad has spoken to him once,” McKenzie says. “Andrew was diagnosed in his late teens. Since then, I have been journeying with that diagnosis single-handedly.

“What I fear the most”, she says, “is what will happen to him after I am gone.”

Inge Petersen, a professor of public mental health at University of KwaZulu-Natal, says: “To help patients live in the community families need to be offered support. Often in low and middle-income countries the money does not follow the patient after they are discharged from hospital.”

In 2016, 95{35112b74ca1a6bc4decb6697edde3f9edcc1b44915f2ccb9995df8df6b4364bc} of the mental health expenditure of the Jamaican health ministry was dedicated to Bellevue hospital, although the facility offered treatment to only 22{35112b74ca1a6bc4decb6697edde3f9edcc1b44915f2ccb9995df8df6b4364bc} of Jamaica’s mental health patients, according to an internal audit.

The policy commitment to deinstitutionalisation is further undermined by 2020 WHO data, which shows that more than 61{35112b74ca1a6bc4decb6697edde3f9edcc1b44915f2ccb9995df8df6b4364bc} of Jamaicans hospitalised for mental illness had been in hospital for more than five years.

Finding a way to reintegrate long-term residents into the community, some of whom have lived at the hospital for more than 30 years, is now Bellevue’s priority.

“It’s not possible to rehome every single resident,” Govia says. “We are working to create a transitional adult care facility.”

However, the hospital relies on NGO cooperation. “We may have the best of intentions”, Govia says, “but we really need to get the buy-in from third-sector organisations to be able to realise them.”

“Countries can have wonderful policies,” says Petersen. “But what is really required is technical support for governments in low and middle-income countries to implement successful deinstitionalisation.”

Petersen would like to see a pool of global funding dedicated to implementing efficient mental health policies, similar to the resources available for treatment of HIV.

Govia’s long-term hopes for Bellevue include a world-class neurocognitive psychiatric facility. She also hopes that the hospital will become an example of successful transformation.

“I would love it if, in the next 50 years, Bellevue would provide insight into how to transform effective long-term care,” she says. “In Jamaica, the resource constraints have led us to find creative and cross-sectoral solutions. Even if the fruits are not fully visible yet, the insight and experience Jamaican psychiatrists can provide are important.”